Archaeologists conducting work on the St Peter’s College estate have made a potentially significant discovery that could add a whole new dimension to our understanding of the earliest history of Oxford, and contribute to the wider history of England in the late ninth and tenth centuries.

For the past several weeks, archaeologists have been able to explore a substantial plot of land adjacent to Canal House between Bulwarks Lane and New Road before construction work on the Castle Hill House Building Project begins; and they may have discovered a section of Oxford’s earliest defences.

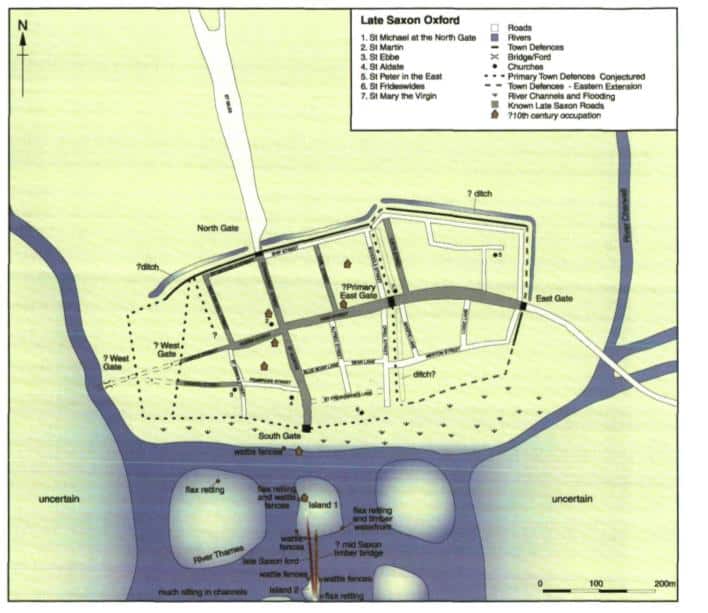

We know that Oxford was first constructed in the late ninth or early tenth century, forming part of a network of burhs or fortified towns built by King Alfred and his son King Edward the Elder to defend what was then known as the ‘kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons’ from the Vikings. The burh consisted of a grid of streets protected by a rectangular-shaped defensive rampart.

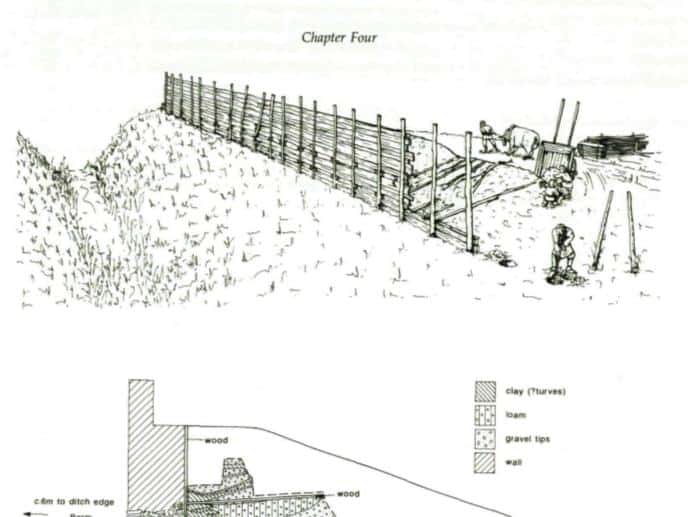

As this map shows, the line followed by the northern section of the rampart is well established, having been observed at various points during earlier archaeological investigations, including a famous excavation on St Michael’s Street, which revealed a substantial section of a rampart constructed from earth and timber.

However, the line followed by the rest of the rampart to the east, south and west is less firmly established, though conjectural reconstructions made before work commenced suggested that it could have passed through our site.

Excitingly, the archaeological work has identified a feature – namely, a deep ditch, similar to that observed at St Michael’s Street – which may have formed part of the western rampart of Oxford’s earliest defences. The angle of the ditch is clearly visible in the photograph below.

The excavation of this feature has revealed pottery associated with it datable to the tenth and eleventh centuries. The ditch seems to run approximately parallel to New Inn Hall Street, which is known to have been laid out in the late ninth or early tenth century and now defines one side of the St Peter’s College campus.

It should be stressed that the emerging evidence remains complex and inconclusive, and more work remains to be done both to recover evidence from the site itself and to interpret the findings.

Meanwhile, however, students and staff of St Peter’s College and a group of interested scholars have recently enjoyed opportunities to visit the site and observe the archaeological work in progress.

If the feature in question was indeed part of Oxford’s earliest defences, they will have witnessed a finding that is of considerable interest and significance, both for the earliest history of Oxford and for wider history the kingdom of England in the making.

Stephen Baxter

Professor of Medieval History

Vice Master, St Peter’s College